Shaykh Ibrahim Niasse: Anti-Colonialism in West African Muslim Consciousness

Beyond Decolonization: The Legacy of 20th century West Africa's Brightest Vanquisher of the Kingdom of Fear

As long as I am a servant to Ahmad, Allah has made it forbidden for my heart to go astray or to submit to an oppressor.

~

Tell the Kings of this earth, may their eyes grow weary, for this godly Dominion [we possess] can never be sold for any dirham.

~

Neither Napoleon nor Lenin and Marx are divinely inspired

So do not be fooled by their theories

But a book revealed by Allah, the Most Glorious and Most High

~

Selected poetry from the many dawawin (anthologies) of Shaykh Ibrahim Niasse

Part I (this is a two part essay)

It is well-known that, after traveling to Europe in the late 19th century, modernist reformer and Grand Mufti of Egypt Muhammad Abduh (d. 1905) came back so impressed with the order and prosperity he saw there, that he famously said: "I went to the West and saw Islam, but no Muslims; I got back to the East and saw Muslims, but no Islam."

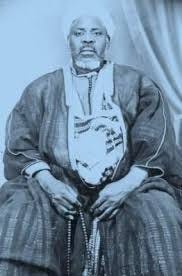

Contrast this discourse with that of the most important and influential West African scholar of the 20th century Tijānī Shaykh Ibrahim Niasse of Senegal (d.1975). I have waited a long time to write about Shaykh Ibrahim Niasse, because it is impossible to do his legacy justice. He is a source of continuous admiration and inspiration and is a teacher and an exemplar that is very close to my heart, which makes it more difficult to write about him. But it is time. The vacuum in Islamic discourse on justice-seeking is so stark and lacking in our present day, that I decided to finally begin explaining the significance of this timeless figure, who spoke about the tumultuous times we are living in and provided an antidote to them.

By now you have surmised that this Substack draws inspiration from the likes of Imam Hussain, Malcolm X and anti-colonial Muslim warriors. Despite their differences, what do the above mentioned valiant leaders in Islamic history all have in common? They Vanquished the Fear within them. They were fearless, effaced in Prophetic love. Not only is Shaykh Ibrahim one of the most important scholars of the 20th century, he was—without exaggeration—one of the most ardent and devoted lovers of the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ to ever live, having written tons of poetry in his praise and lived his entire life in service to his most beloved.

It was through that love that he became a visionary in every sense of the word, and a speaker of truth to rulers and leaders during a tumultuous era. He was a “Walking Qur’an” having at an early age mastered the Qur’an and its interpretation, Hadith, jurisprudence and creed. He traveled across Africa and traversed the whole world, from Karbala to Karachi. He was a voice of truth to presidents and paupers, and enjoyed a vast international network of Muslim scholars from within Africa and globally. People called him a pan-Africanist, an anti-colonial voice, a pan-Islamist, but he was much, much more than just those things. Shaykh Ibrahim’s vision of Islam in the world needs to be studied as its own school of thought and practice. This post is but a drop in the ocean of 20th century West Africa’s brightest light.

To give you but a small taste of his fearless voice and uncompromising positions, In his prolific madih (praise) poetry dedicated to the Prophet Muhammad, he describes his sojourns across the world while constantly praising and longing towards his Beloved ﷺ wherever he is, and even describing waking encounters with the Prophet in these global metropolises. When he mentioned being in Paris, unlike Abduh, he saw no Islam there. He referred to it as باريس دار الكافرين كسالى, “Paris, the abode of the lazy deviants.” (Diwan Sayr al Qalb, Letter Jeem).

Shaykh Ibrahim also famously joked in a humorous audio recording that miraculously survives to this day—in his public tafsir (exegesis) on the Qur’an that were attended by thousands in his mosque in Madina Baye, Kaolack, Senegal, held during the month of Ramadan—regarding this verse in Surat al-A’raf: سَأُو۟رِيكُمْ دَارَ ٱلْفَـٰسِقِين I will show you the abode of the wicked, that, with a lighthearted chuckle, these lands are, in fact, referring to Paris.

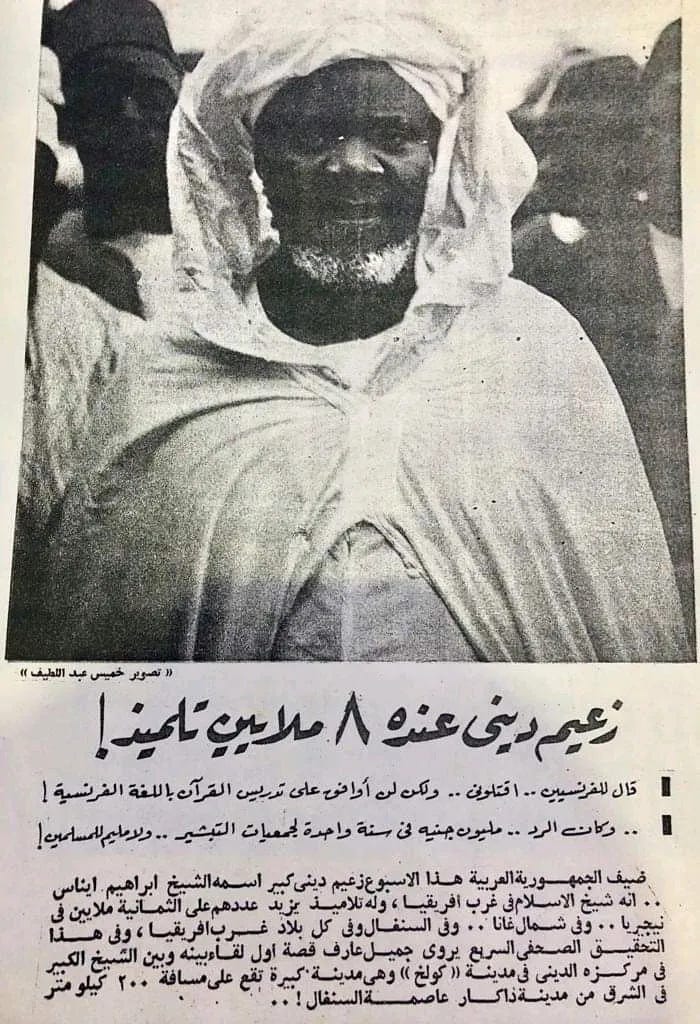

Furthermore, when he expressed interest in studying study French in addition to his formal Islamic education as a young man, his father Abdullah Niasse—a famed scholar in his own right who fought the French colonization of Senegal—did not allow him to study the language of their oppressors. In a similar vein, this 1960s Egyptian newspaper clipping below reads: “A religious leader with 8 million students! He (Ibrahim Niasse) told the French, ‘you will have to kill me before I allow you to teach the Qur’an in French.’ To which the response was, millions of francs in donation to missionary schools in Senegal, and not a dime to the Muslims.”

Unlike Shaykh Ibrahim, for the most part, modern Muslim scholars—since the 19th century onwards—tended to project a Abduh-style dual fascination and loathing towards the West: on the one hand, they would laud its technological, scientific and legal achievements, while simultaneously objecting to its colonial exploitation of Muslim countries and the imposition of its secular values. How come we know very little of alternative Islamic views of modernity, beyond the Modernist and Neo-Traditionalist models? Why is it that Muslims globally know 20th century scholars like Maududi, Qaradawi or Qutb but not Shaykh Ibrahim? Is it due to his blackness? How did someone like Shaykh Ibrahim navigate this tumultuous era? How did he manage to maintain an unapologetically rooted response to Western nation state treachery, Zionism, and the challenges of modernity?

Rather than vying for the ideal of “Judeo-Christian” progress as the pinnacle of civilization, Shaykh Ibrahim—and other scholars from West Africa—saw Islam as their primary reference point. Shaykh Ibrahim Niasse saw the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ as the ultimate model to aspire to, as opposed to an Islam that always needed to “catch up” or “respond” to the secular West. He saw Western hegemony— its so-called values of democracy, progress and order—as nothing but an empty illusion more than a century before the current illusion of the “ruse-based-order” has burst thanks to the Palestinian struggle (here, in my own coinage, I intentionally misspell “rules” as “ruse”).

He was not enamored by the world of forms and the West’s “progress,” rather, he saw it for its true reality: opulent material progress devoid of spiritual wealth, a temporary abode perpetuating disbelief, a system of supremacist exploitation and collective rejection of the final revelation to humanity. In his famous essay, Africa for the Africans, he opened his statements by comparing colonizers to idolaters, because they “believe in something that neither hears nor sees, a non-living object, something that is but the creation of Allah and a construct of man himself, such as the cross, pictures and statues.”

At a time when everybody else was trying to find their place in the brave new world of the nation state system, to get a “seat at the table” or recieve petty crumbs from the Leviathan world order, he did not play into the identity politics du jour, nor did he mince his words to try to bridge constructs of “East” and “West” or “modernity” vs. “Islam.” He did not engage in apologetics to prove that Islam is “moderate”, (read: malleable); a de-fanged version of faith that has done away with shari’ah and jihad.

Instead, through being a living, realized inheritor of the Qur’an and the sunna, he felt no need to “react” towards Europe or “the West.” He simply acted. He saw worldly, material power as a veil and a smokescreen. He could transcend its veneer of perceived superiority, because Islam was not simply a worldly ideology for him to advance mundane political interests. Rather it was about an arduous, and sincere path journey to the Divine. A lived reality and a continually giving source of prophecy and revelation. You could say that through this worldview that centers activated faith and spiritual actualization (tahqiq), he went beyond de-colonization altogether, because even under Western hegemony and the ṭāghūt (idol) of nationalism, his spirit was was already free.

That is not to say that Shaykh Ibrahim was anti-progress, technology or commerce; quite the contrary, he has penned prescient essays and has given speeches about the merits of radio technology and cutting edge space exploration. He also lauded the importance of just rule as the basis for governance, even if the ruler is a disbeliever, while at the same time, shunning secular rule and maintaining that the ideal ruler is a just and righteous Muslim “philosopher-king” or khalifa.

Shaykh Ibrahim saw might and progress through the all-encompassing sovereignty of God, via a methodology of direct, experiential knowing of the Divine (ma’rifa). To most, this esoteric rhetoric is antithetical to advancing earthly power, but to sages like Shaykh Ibrahim, worldly power was not an idol, nor was it shameful to take on positions of worldly leadership. As such, to him, Sufism is not an impediment to worldly influence, rather, it is the way to a more just and peaceful world because one’s Islam becomes devoid of attachments, defects and blemishes. Consider this segment from his tafsir (exegesis) of the Qur’an on his conception of what religious scholarship is truly about, and in turn, what a religious scholar (faqih) should actually aspire to represent:

Allah described the cream of the crop among the believers by saying: Among the believers are the rijal who have proven true to what they pledged to Allah. Some of them have fulfilled their pledge in this life, others are waiting their turn. They have never change in their commitment in the least (Ahzab: 23) and Allah has also said about them: When the believers saw the enemy alliance, they said, “This is what Allah and His Messenger had promised us. The promise of Allah and His Messenger has come true.” And this only increased them in faith and submission (Ahzab: 22).

Such is the affair of one who attaches themselves to God firmly, not faltering when the choppy waves of strife (fitan) come their way. This condition is reserved for those who truly Know God, and this is what constitutes true fiqh (understanding) in religion. Through this, the purity of certainty descends [upon them], and [they come to know] the very core of understanding in religion. This process entails the gradual manifestation of God’s descriptions and hidden names on them, and perfecting the fulfillment of their rights and etiquettes.

This is [real] fiqh (understanding of religion), and it is outside the circle of the realm of the jurists. It can only be reached by the the Prophets, the Knowers of Allah and the Sincere Righteous Ones (siddiqun). This is the type of understanding that is referred to in the Prophetic Hadith: “Allah is not worshipped by anything better than [a sound] understanding of religion. A single faqih is more hated by the Devil than a thousand worshippers.” (Riyad at-Tafsir of Shaykh Ibrahim Niasse, Vol. 3, p.327)

Because of racial prejudice towards black scholars as somehow being “less knowledgeable” or “less authentic” than their Arab counterparts, many Muslims around the world and in the West are oblivious to the richness of Islamic scholarship from the African continent. Many do not know that, for example, when the great West African scholar and ruler Hajj Umar Futi Tal (d.1864), (the figure whose scholarship I wrote my PhD dissertation on), passed through the seat of Islamic higher learning in Egypt, Al-Azhar on his way to hajj, where it is said that the most knowledgeable scholars of Cairo quizzed him for hours on various subjects and Islamic sciences. They felt that a black man could not possibly know more about Islam than they did. Legend has it that not only did Tal recite the Qur’an in its entirety, he was also able to list exactly how many times each word appeared in it. He dazzled the Azharite elite and was a walking testament to the fact that West African scholars erudition in Arabic and Islamic studies matched—if not exceeded—that of their Arab counterparts, while having never left West Africa to receive their education.

Similarly and a little over a century later in 1961, Shaykh Ibrahim Niasse was the first West African to have led al-Azhar Mosque in Egypt in Friday prayer, after which he was dubbed more formally with the honorific, "Shaykh al-Islam", which is considered the highest and most prestigious honor any Muslim scholar can achieve. His spiritual and scholarly prowess did not go unnoticed by contemporary Arab scholars. In a letter by Secretary General of the Muslim World League in Mecca, the late Meccan scholar Muhammad Surui Al‑Sabban wrote to Shaykh Ibrahim in 1961, commending his preservation of the Qur’an and sunna as the closest resembling form to the way of the Prophet and his companions:

The pioneers have left the Hijaz, along with the propagators of the religion. They also left with the jurisprudence (fiqh) of the Hijaz, and now it remains with you, Shaykh Ibrahim. […] Indeed, you are of the real people of Medina in both fiqh and Qur’an. These are the proofs of your steadfastness, and it is not the pride from within me, but the pride is for you and by Him. You have believed and steadfastly you have protected and spread the religion and become victorious.

This Substack has amply discussed scholars who fall short of their ethical and religious commitments due to pernicious state politics and interests. For this post, I wanted to focus on a more positive model of Islamic scholarly authority instead, those who uphold the mantle of those who Vanquish the Kingdom of Fear. Shaykh Ibrahim was thus not a polemicist or an ideologue, he was universal in his vision for humanity, without comprising on his commitment to Islam, following the way of the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ who was sent as “a mercy to all humankind,” not just one’s sect or group.

In the practical sense, he not only helped found the Muslim World League in Riyadh and the High Council of Islamic Affairs in Egypt and Karachi, he also maintained close relations with several prominent leaders in the independence movements during the 1960s, such as Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana, Ahmad Sekou Touré of Guinea, the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem Hajj Amin al-Husseini, Gamal Abd al-Nasser of Egypt and many others. Biographers who reference these encounters often gloss over the fact that, Shaykh Ibrahim acted as a hujjah (proof) towards them, and did not want anything from them. Rather, he was either a source of spiritual salvation for them—or torment—if they failed to heed his sound advice.

According to oral accounts, Shaykh Ibrahim sent a letter to Abdel Nasser imploring him not to execute the Muslim Brotherhood leader Sayyid Qutb, stating that whatever their political or doctrinal differences, Qutb was a fellow Muslim and did not deserve to be executed by the state. The Egyptian president nonetheless went ahead with the execution, warranting the extreme disappointment of Shaykh Ibrahim, who, upon visiting Nasser’s grave after his death, pronounced his concern over state of Abdel Nasser in the afterlife.

The Palestinian struggle was his central concern, and part II of this essay will elucidate his views on Zionism and Palestine. Shaykh Ibrahim deserves the serious attention of Muslims perplexed by our current condition, because he represents the Prophetic archetypal scholar that managed to stay afloat during the century in which the “ruse-based-order” came to be set in stone, and arguably, constituted the rotten basis for the pervasive systematic treacherous world order we are currently living in. The century of “isms”: nationalism, communism, secularism, Salafism…etc.

It is because of this fearless, non-reactionary disposition that whenever I teach a course on the rich history Islam in West Africa, I make sure to entitle it: “Beyond Decolonization.” I suggest that this framing is pertinent to the Palestinian struggle and other ongoing anti-colonial struggles in Kashmir, Xinjiang, Mianmar, Sudan, Yemen and Congo. The histories, writings and legacies of Muslim scholarly figures from the African continent have the potential to offer an antidote to much of the globalized culture wars and identity politics that plague much of the discourse of our time. Of course, some might argue that this is an overreach. That no singular notion of “history” of any region is so homogenous that it can present a counter narrative.

But I have seen enough unique patterns and approaches to Islam in West (and certainly East) African scholars and sages throughout the 19th and 20th centuries that set them apart from their Arab counterparts at a time of contentious nation-state formation and so-called “independence” from colonial rule. When any student of the so-called “Modern Middle East” is taught the history of Islam in the aftermath of the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, we are simply taught the modernist rhetoric of Muhammad Abduh, Rashid Rida, Jamal ad-Din al-Afghani and others who, by-and-large, based their projects on a reaction to the West’s rising domination and hegemony. In more recent scholarship, more attention has been paid to Neo-Traditionalism, which is still a reactionary movement to “bad” modernity.

What we tend to focus much less on as intellectual historians of Islam, is the model of those who were not so busy re-acting to—insert epistemic threat here— secularism, Wahhabism, materialism, modernity, critical theory, Trump, gender hysterics, what have you. Rather, I focus here more on those receptacles of Prophetic light who were simply busy being. Their simple act of being is in itself a revolutionary act.

Therein lies all the difference. If a scholar devotes his intellectual life to responding to modernity, Zionism, communism, wokeism…etc (fill in the blank with ideology du jour), he/she will always be in a position of weakness because the basis of their project is on the defense. By constantly responding to external ideological waves, a unique, standalone project cannot stand on its own as shining alternative in any era. It can never succeed in modeling an embodied, organic, primordial model or way of being in the face of external storms.

When one operates from a place of actualization, in which their words match their actions: they become one with the One, in complete, perfected alignment. This affair starts on the level of individual, as Islam’s message was always directed to the individual first. As such, one whose knowledge is activated through positive action, leads to a state in which ones’ inner reality, and rational knowledge, matches their outer state and their actions (عامل بعلمه). That state describes the true khalifa (inheritor) of Allah, one who accomplishes their true primordial mission of being aligned with celestial command in every deed, word and action.

Getting to this station, of course, is a matter of pure grace, of love, evoked in this Hadith Qudsi in which Allah says:

When I love a servant, I become his hearing with which he hears, his sight with which he sees, his hand with which he seizes, and his foot with which he walks. If he asks me, I will surely give to him, and if he seeks refuge in Me, I will surely protect him. (Hadith 38, 40 Hadith an-Nawawi)

Herein lies the crux of the matter. Can anyone blessed enough to achieve this state, someone whom Allah loves so completely and perfectly that they come to be the eye in which He sees, the ear in which He hears, the hand in which He strikes, be a match for any worldly “ism”, force or power? Surely, these smokescreen powers would seem so fickle in face of such activated, embodied vessels of light. No earthy power can begin to contend with this type of person, the friend of Allah, for whom Allah declared warfare towards anyone who shows enmity to them, in the beginning of the same Hadith Qudsi above: “whosoever shows enmity to a wali (friend) of Mine, then I have declared war against him.”

Thus, it is this type of saintly disposition—this effacement in Allah as the true source of all power—that describes the revolutionary lives of Shaykh Ibrahim Niasse and those like Hajj Umar Tal, Usman dan Fodio and their sagely inheritors, which thankfully still continue this tradition of living, non-reactionary, rooted Islam to this day in communities globally.

Perhaps this is the type of victorious faith that the Prophet ﷺ was referring to when he said that in the end of times, “the sun shall rise from the West.” There is so much that can be said about these black Muslim exemplars, and how their teachings can be antidotal to the contemporary prevalent Muslim, Arab and American scourge of ethnic chauvinism and racism, but let that be for another time.

And I have gained a union which obliterated my Self

It is around him (Muhammad) that my heart revolves

Even if I happen to go about other things

For nothing exists except Allah

I reached this certainty when my veil was removed

Upon him Allah’s peace along with his blessings

Only Ta Ha makes me rejoice, for he is my treasure

May Allah's peace and blessings as a seal of this poem

Be upon his household and upon his companions.

-Shaykh Ibrahim Niasse, Sayr al-Qalb, the Letter Lam, 1968.

*The next part of this post will be entitled, From West Africa to Al-Quds: The Question of Palestine. It will cover Shaykh Ibrahim Niasse’s rousing views on Palestine, Al-Aqsa and Zionism. Subscribe to make sure you don’t miss it.

For further reading and academic sources on Shaykh Ibrahim, consult:

Rudiger Seesemann, The Divine Flood. Ibrahim Niasse and the Roots of a Twentieth-Century Sufi Revival, Oxford University Press, 2011.

Zachary Wright, Living Knowledge in West African Islam, Fayda Books, 2018.

Zachary Wright, Pearls from the Flood: Select Insight of Shaykh al-Islam Ibrahim Niasse, Fayda Books, 2015.