Vanquisher of the Kingdom of Fear

How 18th & 19th century North and West African scholars gave us a way out of this darkness through a living connection with the Prophet ﷺ

A knowledgable elder in my family posited this thought-provoking rhetorical question on his social media page: “my question is directed to the Egyptian government: if the Prophet ﷺ himself was sieged in Gaza under conditions of thirst, famine and bombing right now, what would you do?”

My answer?

They wouldn’t care. They wouldn't care because repressive states have already shown us that. Nothing will shame them out of their callous greed and treachery. They are announcing to us with every action, word and stance they they have no fear of God and His Messenger. If they did care, they would not be accomplices in this shameless extortion, strangulation and genocide of Palestinians. They have more fear for their own interests, worldly power and Big Brother in charge. Their calculus has nothing to do with ethics, morality or religion. Their very existence is predicated upon blind subservience to the earthly powers-that-be, so why would it make any difference at all to them whether the Prophet himself ﷺ was among the people of Gaza?

More importantly, the Prophet ﷺ is already there, among them. The burial ground of the Prophet’s Great Grandfather, Hasim ibn ‘Abd Manaf is the ancestral source of the prophetic heart of Gaza. The Prophet is there, every time a father cries to the heavens, overlooking the shrouds of his family, calling out, “send our salam to the Messenger of Allah! Tell him your ummah has failed you oh beloved of Allah!” The Prophet is there every time a wounded martyr’s mother tearfully cries, “fidak (anything for you) ya Rasul Allah!”

He ﷺ is in each act of worship he commanded they perform: a janaza prayer, Juma’a over the rubble of a millennia old mosque and fasting only to break fast on a can of chickpeas and lemons. He is there when the adthan is whispered into the ears of a baby named ‘Muhammad’ who has just been born in a tent, as a sign of hope and defiance.

He is there, every time the forehead of a crying child is kissed. He is in every syllable of Qur’an recited under bombs and between shattered limbs. He is already there, in Gaza, in Sudan, in Yemen, in Guantanamo Bay, in Uyghur concentration camps and in the dungeons of Arab state prisons. He ﷺ is “in us” both literally and figuratively:

Know that Allah’s Messenger is still in your midst. (Qur’an 49:7)

&

The Prophet is closer to the believers than their selves (Qur’an 33:6)

This is not some esoteric reality, though if you are curious about the metaphysical, pervasive, primordial presence of the Prophet, look up what sages like Ibn Arabi and others have said about the haqiqa Muhammadiyya. To keep things simpler, “he is in us” can be understood in the same way of this Hadith Qudsi:

Allah will say on the Day of Judgment, ‘Son of Adam, I was sick but you did not visit Me.’ ‘My Lord, How could I visit You when You are the Lord of the Worlds?’

‘Did you not know that one of My servants was sick and you didn’t visit him? If you had visited him you would have found Me there.’ Then Allah will say, ‘Son of Adam, I needed food but you did not feed Me.’ My Lord, How could I feed You when You are the Lord of the Worlds?’ ‘Did you not know that one of My servants was hungry but you did not feed him? If you had fed him you would have found its reward with Me.’ ‘Son of Adam, I was thirsty, but you did not give Me something to drink.’ ‘My Lord, How could I give a drink when You are the Lord of the Worlds?’ ‘Did you not know that one of My servants was thirsty but you did not give him a drink? If you had given him a drink, you would have found its reward with Me. (Bukhari)

If Allah is closer to the believer than their jugular vein, and the Prophet is closer to the believers than their own selves, and if, per the Qur’anic understanding he ﷺ is “still in our midst”, this would mean that when every drop shed from a believer is a direct attack against the Prophet ﷺ himself.

But our understanding of events today is so far removed from this idea. That is because of our ignorance and the way we’ve accepted this political system in which God and His Messenger ﷺ are not the ultimate guiding authorities in this temporal realm. We have been subdued by the external reality of this deformed system in which ‘might makes right,’ so that what is true and just matters not in the face of worldly, mundane power. In essence, our very existence and imaginations are gripped by what I call: the Kingdom of Fear.

The ‘Kingdom of Fear’ is the global political system we are currently living under. It is foremost a mental occupation: it renders even our own unique Islamic vernacular, narrative and view of the injustice completely paralyzed and forbidden under the hegemonic, demonic grip of the ‘axis of compliance’ and ‘state fundamentalists’. As Edward Said wrote, “imperialism is decided in narrative.” Since their inception, secular Arab and Muslim-majority nation states have done the bidding for empire and lulled and drugged their masses with their state-compliant religious institutions that control and regulate all public discourse on Islam. It is not difficult to see who exactly all these decades of repression, tyranny and injustice ultimately benefit: since the fall of the Caliphate about a century ago, nation states became proxies for Western-Zionist hegemonic interests and thus became fully subservient to the legion of the devil: overlords of the Kingdom of Fear.

It is only the devil who would make men fear his partisans. Fear them not; fear Me, if you are true believers. (Qur’an 3:175)

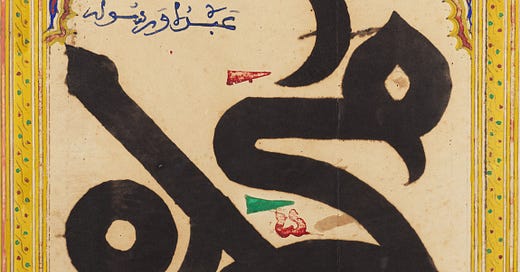

This brings me to the key point of this post: the only antidote that is able to obliterate the Kingdom of Fear—the only way out of this Shaytanic grip, the only thing that can smash its devilish minions—is the Master of the Two Worlds, Leader of the Banner of Praise: Muhammad ﷺ. After all, his central, polar authority is undisputed and outlined in all of Islam’s doctrinal sources, even he said of himself ﷺ:

I am Muhammad, I am Ahmad, I am al-Mahi through whom Allah obliterates unbelief, and I am Hashir (the gatherer) at whose feet people will be gathered, and I am 'Aqib (after whom there would be none), and Allah has named him as compassionate and merciful. (Sahih Muslim)

Similarly:

I am the master of the children of Adam on the Day of Judgement, and I am not boasting. The Banner of Praise will be in my hand, and I am not boasting. There will not be a Prophet on that day, not Adam nor anyone other than him, except that he will be under my banner. And I am the first one for whom the earth will be opened for, and I am not bragging. (Tirmidhi)

The Gaza genocide has brought about a lot of messianic rhetoric: Christians are unapologetic about their narrative of “Christ as King”, Jews are unequivocal about their status as “God’s chosen people” and are hellbent on eradicating all “amalek”. As such, Muslims can no longer afford to be hesitant about claiming the living message of the liege of all prophets enshrined in the metaphysical presence of Muhammad ﷺ.

Allah has decreed, “I and My messengers will certainly be victorious.” (Qur’an 58:21)

How a Harvard Seminar Taught by a German Orientalist Changed my Life

Let me explain the importance of this reality by telling you a bit about a philology seminar I took in 2015 that was taught by respected German legal scholar Baber Johansen, who is now retired from the Harvard Divinity School. This course got me hooked on studying Islamic and Sufi texts and set me on the path of lifelong research I am on now. It was about 18th and 19th century intellectual currents —mainly from North and West Africa—and it was entitled “Islamic Modernism: Part I.”1 Not the most exciting title I suppose, but it offered a portal to a discourse sorely missing from our present day mainstream narrative on Islam. We read primary texts in Arabic from South Asia to North Africa, mainly by Sufi scholars. At times, we did not understand what linked all these texts together, but it became clearer once it we started to weave one, big, important intellectual and spiritual current that constituted Muslim scholar’s first collective “response” to modernity.

In this seminar, we asked: before colonialism and the nation state system ravaged the world, what methodologies did Muslim scholars outline for a viable and healthy spiritual life for a Muslim? What questions consumed them? Why was mysticism so central to their approach? Previously seen a period of “intellectual decline,” recent scholarship has shown that it was far from it. In fact, the 18th century was among the most spiritually and intellectually invigorating eras in Islamic intellectual history. The enigmatic figure of “the Seal of the Saints” appeared in 1782 in the figure of the North African Shaykh, Ahmad Tijānī. His way spread like wildfire in West Africa and is considered the largest Sufi order in the continent today. Most Western academics of Islam recognize that time as being a time when “tariqa Muhammadiyya” peaked, and became popularized and mainstream. The idea being that the Prophet is the ultimate Shaykh, guide and leader and that a continuous, lived connection with him is not only possible, but necessary.

This era also brought with it invigorated intra-Muslim debates on mysticism and Islamic law. Could you imagine a Wahhabi scholar and a Sufi scholar sitting together in a reasoned, good will, respectable debate today? With both camps so crystallized in their schools of thought and so hardened by security state politics and ideological chasms? Well, this is exactly what happened at the initiative of Moroccan mystic and theologian Aḥmad ibn Idrīs, (d.1837) who was considered one of the most dynamic personalities in the Muslim world in the 19th century.

Unlike most Ash’ari Sufis today, Ibn Idrīs left Fes because he saw Moroccan jurists there as too mired in taqlīd and he categorically rejected the sole authority of the established schools of jurisprudence. On this mutual basis of unlikely alignment, he immigrates to the Hijaz to dwell among scholars who focused more on Hadith and ijtihad, and co-existed with them. We have record of him entering into a debate with a Wahhabi theologian in the Yemenite city of Sabya in 1832. Though their views and differed dramatically, there were no securitized accusations of “bad Muslim” being slung between them under the gaze of state-sponsored definitions of Islam. (You can read about this debate in his text, Risālat al-Radd 'alā ahl al-ra'y which was translated to English by brilliant German scholars.)

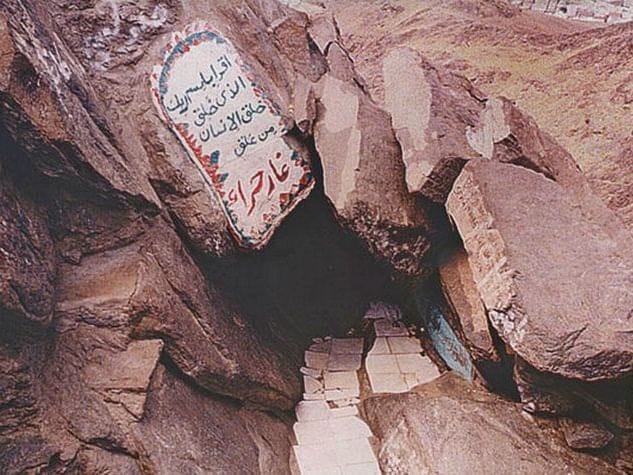

More importantly, most sages and scholars of centuries past always stressed this unassailable allegiance to the Prophet as a living, continuous, presence. The 13th century Andalusian scholar Abu al-Abbās al-Mursī who became one of Egypt's four patron saints, said that “if the Prophet ﷺ were absent from me for even an instant, I would not count myself among the Muslims.” Similarly, the 18th century Moroccan saint al-Dabbāgh, who, though illiterate, relayed his accounts about the unseen Diwan al-Awliya’—the so-called “Council of Saints”, the gathering of saints, both dead and alive, who presumably convene in the cave of Ḥirā’ with past prophets, companions and sagely figures like al-Khiḍr—to discuss pressing matters related to the ummah.

Al-Dabbāgh can easily be dismissed as insane, a heretic or a charlatan today, but he was a central figure in outlining clear and verified methodologies for a Muslim to witness the Prophet ﷺ in a waking state, describing it as a matter of love and exertion: “to the point where he is never absent from his mind, and no distractions or concerns divert his attention from him. You see him eating while his mind is with the Prophet, drinking while he is like that, arguing while he is like that, and sleeping while he is like that.”

This kind of devotion was part-and-parcel of a holistic view of what constituted a good Muslim scholar. One was not complete without this living, experiential love. In his book, Realizing Islam, Zachary Wright reveals that Maliki scholars in Timbuktu were regularly described as having characteristics being endowed with maʿrifa, sainthood (wilaya), and having visionary encounters with the Prophet Muhammad. The fifteenth- century Timbuktu scholar Yaḥyā al- Tadillis is described as “the jurist and scholar, the quṭb, the Friend of God Most High” who saw the Prophet in dreams regularly. Such descriptors indicate that seeing the Prophet in visions was a regularly recognized, normative feature of pious ‘ulamā’ in West and North Africa.

Where did this vernacular go? How did we let the Kingdom of Fear rob us of the second part of the shahada in its realized, full bodied potential? Why did we lower our standards of prophetic and moral excellence for our scholars? Was the secularist rupture of contemporary Muslim societies so violent, so mired by the ideological reactionary impetus, that it took away our very life raft as an ummah, the possibility of a living connection with the Messenger ﷺ?

Now such statements are considered heretical and fantastical, when at the cusp of colonization that ravaged the Muslim World—in the 18th and 19th centuries from South Asia to West Africa—we see a very strong effort wherein scholars were trying to make this knowledge more mainstream. As mentioned prior, Orientalists called this movement, tariqa Muhammadiyya, but scholars have shown it wasn’t really an organized movement per se and it wasn’t something new in essence. It was simply long-standing, existing central Islamic teachings on the Prophet ﷺ packaged more accessibly for Muslim masses, who were increasingly becoming cut off from such knowledge. They were trying to tell us something important: they were throwing us a rope to stay safe from the ravages of the Kingdom of Fear. This approach was seen as a safety net: when the Prophet ﷺ is centered, worldly mirages will be automatically be dwarfed in the eyes of sincere lovers, be they a scholar, a jurist or an average believer.

This powerful, universal and unifying force in the figure of the Prophet ﷺ has been betrayed today by the clerical class of contemporary Islam and the so-called Sufis who have been co-opted by state fundamentalists. Those who deify the construct of “tradition” and claim prophetic love while benefitting from shady commitments with tyrants while the ummah burns. (Read my previous post: “Mawlid Mubarak from the Sacred Lands.”)

The Muhammadan Way was nothing new in the sense that it is simply a personified, embodied Islam, just as Muhammad ﷺ was the personification of the Qur’an. But the Muhammadan Way was also revolutionary: it had several corrective, reformist characteristics when it became popular in the 18th and 19th centuries. It was an antidote against scholarly and political decline and tyranny. It brought with it great diversity in legal positions and opinions, and enabled scholars to enliven the shari’a not just through past texts, imitation, and “traditional sciences” only (though those were still central of course) but with a viable, living, and verified connection to both Allah and His Prophetﷺ . 2

Recall that the reason Imam al-Busīrī composed the famous poem, al-Burda, was that he got so ill that even the doctors could not treat him, so he thought of composing a work that could earn him the intercession and pleasure of the Prophet ﷺ . After he wrote it, he saw him ﷺ in a dream, wiping over him with his hands and when he woke up was cured. If one poet was cured by this act of devotion, and his poem became the most recited poem in the world, then imagine what would happen if he could wipe over the whole world and remove its ailments? Imagine if every Muslim longed for the Prophet for a cure for themselves and the world in this way? What if we made Prophetic love the only way out of this darkness? What if we made Muhammad ﷺ the remedy for the collective agony plaguing humanity?

In these times of grave darkness, all arrows must point to the Prophet ﷺ, the wellspring of wisdom, the ultimate guide, the continuously praised one, and the undisputed leader and intercessor of all of humankind—no matter their race, sect, creed, or madhhab. This type of understanding, this reality has been so erased—rendered so unseen, so unspeakable and absent from religious discourse—when it was once the central calling cry for these sagely authorities at the turn of modernity. So let us wrestle back our narrative from the godless empire, since war is won first in the realm of imagination. Let us smash the idol of the Kingdom of Fear and resurrect instead the Kingdom of Love, of Mercy and of Justice.

This journey can only begin when we truly heed the message: “that Allah’s Messenger is still in your midst.” (Qur’an 49:7).

I was far less interested in the class “Modernism: Part 2” which was mainly about the writings of Abduh, Afghani and Rida and other proponents of the salafiyya as a reactionary reform movement. I think this constitutes much of the discourse on Islam and modernity and I felt saturated, if not fed up, with this approach.

This path has a long history, a methodology and an etiquette, and I caution you not to embark on it alone. It is a science, a way of life, and it continues to exist in this day and age in various pockets in parts of the Muslim world like West Africa and in the embodied presence of living saints in places known and unknown.