The Forgotten Islamic Atlantic Revolution

Years before the French Revolution, West African Muslim scholars founded states that centered justice, abolition and knowledge production. We desperately need this missing piece of modernity's puzzle.

My connection to Muslim West Africa began even before I realized it.

My maternal grandmother, an elegant matriarch hailing from the Little Damascus of Palestine, Nablus, was from the well-known Takruri family. I recall inquiring about the origins of the name Takruri, and a family member attributed it to the Arabic root word for “repetition”, tikrar, as a reference to someone who would constantly “repeat” the dhikr (rememberance) of God.

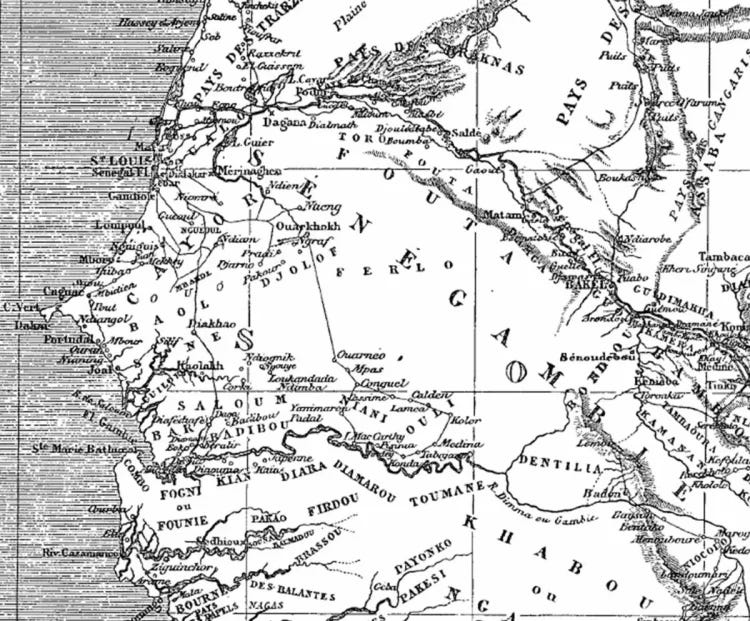

Later in my graduate work, I realized that Western Bilad as-Sudan, or modern-day Muslim West Africa, was historically called, Bilad at-Takrur, and that a Takruri was also the term used to refer to West Africans who made pilgrimages to the Holy Land, Palestine. Today, Arab and African writers refer to all of the Western Sudan simply as Takrur, in reference to the historic Kingdom of Takrur which was located on the lower Senegal River.

Whether I had a West African ancestor that moved to Palestine generations ago, or an ancestor that remembers God much, both possibilities are in essence one and the same thing, and point to a common source. After all, there is scientific consensus that all of us originate from Africa, and dhikr is the primordial way of being: the original blueprint for humanity to return home. To return to the Source.

Sometimes, the term Takrur is specifically associated with the Futa Toro in Senegal—the region that is home to the Sufi warror scholars like Hajj Umar Futi Tal (d.1864) whose work and legacy I would come to devote my doctoral research to. It is said that “Futa Toro” is derived from a Fulani expression meaning “abandon idol worship,” where futa means “abandon” and toro means “idols,” even though futa is closer to Arabic than Fulani. Others claim the name originates from the first ruler of Futa Toro, “Ja Aka”, in reference to someone who possibly from no other than… the city of Acre (Akka) in Palestine (!) whose name evolved into Futa Toro.

Iconoclasm.

Dhikr-centered notions of humanity.

Hints of a possible Palestinian connection.

Just-rule based on Muslim scholarship.

It is not hard to see why Muslim West Africa, or, Bilad at-Takrur, wholly enraptured me.

Studying this region and its Islamic character was a matter of alchemical destiny. But it was not simply about these personal, unlikely connections. Rather, it was the sheer breadth of revolutionary political legacies rooted in Islamic scholarship that demanded my full research attention. Sadly, these legacies have been repeatedly ignored by Muslims and non-Muslims alike out of racialized prejudice towards Africa and African Muslims.

The region of Futa Toro stands out among other Senegalese regions for its early adoption of Islam, well before Almoravid invasion. According to oral tradition, Islam came to West Africa with the army of Uqba ibn Nafi’, the companion of the Prophet Muhammad in the 7th century—who is also the ancestor of Senegal’s notable Cisse scholars. Islam would naturally and organically take deep root in the region by the early 11th century, with Futa Toro becoming home to many of Senegal’s foremost religious and intellectual visionaries.

Manumitting Humanity: the Forgotten Abolitionist Atlantic Revolution

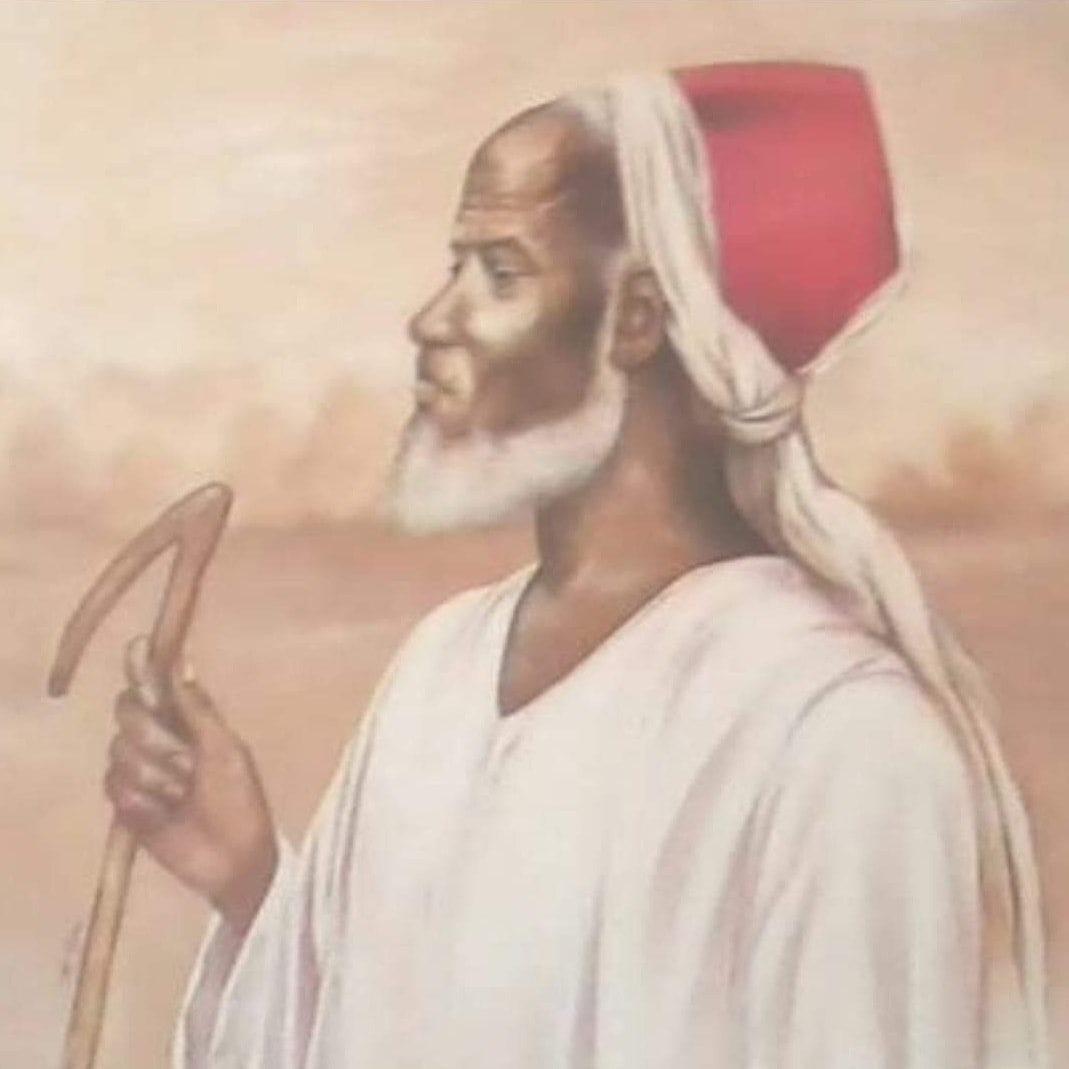

What is arguably the most defining feature of the Futa Toro region is that it is home to the first Atlantic revolution: the forgotten Islamic revolution of the 18th century. Based on Islamic scholarship and principles, during the American revolution (1775-1783) and years before the French revolution (1789-1799) the Muslim scholar and jurist Cerno Suleyman Baal (d.1776) would lead a revolt against the corrupt rule of the Deniyankobe regime to found historic Almaamy States: caliphates that centered the pursuit of justice that were ruled by Muslim scholars, or, almaamys (which comes from the word, Imam).

During the 19th century CE, the African continent in general—and West Africa in particular—witnessed a wave of reformist movements aimed at spreading Islam in the region and reviving the practices and institutions of the faith that had eroded over time. After the decline of major Muslim empires such as the Sokoto Caliphate and the Mali Empire and the encroachment of Western colonialism, preserving the true spirit of Islam was seen as imperative by local scholars.

These Almaamy States of the 18th-19th centuries centered justice, the abolition of slavery and a mode of rule based on the highest ideals of Muslim scholarship and virtue ethics. Euro-centric narratives purposefully neglect this pioneering Islamic Atlantic revolution that came well before the European revolts for freedom and liberty. Both Western and Islamic histories erase these Muslim liberationist scholars, though they arguably represented a moderate ideal of Islam and revolution for the modern age.

Unfortunately, not much is known about Suleymaan Baal today. He is not discussed in our seminaries, masjids, and colleges today as much as other 18th century scholars such as Abdul Ghani an-Nabulsi or Mulla Nizamuddin. But he arguably managed to do what no other Muslim scholar counterpart could in his age: as a scholar and jurist, he founded Imam-led States through an extensive Islamic reform movement against the perceived corrupt Deniyankobe regime, and established a polity governed by the most knowledgeable and most ethical scholars. This would become the model of Almaamy states, or dawlat al-a'imma.

Not only was Baal’s state the first in Futa Toro to fully implement Islamic law as its code of governance, it built mosques, encouraged literacy and scholarship, more imporantly, it prohibited slavery decades before it was abolished in Britain based on the inherent sanctity of enslaved Muslims. On one occasion, before he launched his revolution, Baal boarded a boat to the Senegalese city of Saint-Louis (Andar) with a young man in chains who was reciting the Qur'an. When Baal asked why he was bound, the youth replied that he had been sold into slavery. Baal challenged those who sold him by insisting:

“I am not beholden to the will of an evil drunkard like you, who starves the poor and allies with the enslavers, the British and the bloody colonizers.

All this earth belongs to God and each one if free to roam it as they please.”

The boy was quickly freed and returned to his Qur’an lessons.

His efforts to end the slave trade are seen more evidently still, in the legacy of his successor, the more well-known Imam Abdul Qadir Kan (d.1806), who is famous for his thunderous declaration to the French trade commissioner in Saint Louis:

“We warn you that anyone who comes to us to engage in the slave trade will be killed. And the same applies if you do not return our children who are in your hands. We absolutely do not want you to buy Muslims — not directly, nor indirectly.”

In his book, the Walking Qur’an, Bilal Ware cites how, “the enslavement of the bearers of the Qurʾan galvanized resistance to the enslavement of Muslims.” (Ware, p. 214). In other words, Baal and his successor, Almaamy Abdul Qadir Kan, instituted an abolition movement based on Qur’anic principles and Islamic jurisprudence:

“Evidence suggests that in 1787, when the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade held its first meeting in London to discuss how to gradually end the trade, the Almaamy ʿAbdul-Qādir Kan had already abolished it in Senegambia. The British did not abolish the slave trade for another twenty years. ” (Ware, p. 219)

The Almaamy States of Futa Toro, can truly shine a light upon our current moment of mass mental and spiritual enslavement, at a time when historical models of notions of just and ethical Muslim rule seem like a long-lost pipe dream. History is always a salve for narrow thinking. It provides an expanse that can break the clasps of tunnel vision. As Marcus Garvey said, “a people without the knowledge of their history, origin, and achievements is like a tree without roots.” Without knowing our roots as Muslims, we are neither able to envision a different future for ourselves nor humanity. Beyond cliche invocations of a “golden” Muslim past, we must center histories that are both relevant and useful to the present day epistemic and civilizational battles over narrative.

French colonial historians commented on the success of the Almaamy states by describing the success of “black Mohammadans” in “making the Qur’an their constitution and establishing a mode of governance that is a blend between being a theocracy and a scholalry-warriorship.” One of they key propagators of the French Revolution, Jérôme Pétion de Villeneuve (d.1794) even said of Baal and Kan:

“The West African Muslim priests (scholars) derived their rule from light, a light that was not given to anyone before them. These wise men refused our gifts, forbade us from trading slaves from their region, and even denied entry to our tradesmen in their lands.”

This light Villeneuve saw was unmistakably embodied in the scholar, warrior and ruler, Sulayman Baal, who set out a clear and well-defined project for establishing a just Muslim state at the cusp of colonial encroachment. If written by a Frenchman or an Englishman, or even an Arab Muslim scholar, this declaration would be seen as enshrining the highest ideals of constitutional law and governance, yet, it is verifiably neglected. Why is that? And who stands to gain from erasing this history?

The constitution for Baal’s Almaamy state was as follows:

“Indeed, victory is with the patient. I do not know whether I will die now or not. But if I do die, then look for a just, God-fearing and pious Imam—one who does not accumulate wealth for himself or for his descendants. If you see that he has amassed wealth, then remove him from power and seize his possessions. If he refuses, then fight him and drive him out, so that the rule does not become hereditary, passed down among his children. Instead, appoint someone else in his place from among the people of knowledge and righteous action, from any tribe. Do not confine rulership to a specific tribe, lest they claim inheritance. Rather, give leadership to whoever is most deserving.” 1

Imagine if this constitution were upheld in the US today, to safeguard it from the interests of greedy and supremacist oligarchs. What a different world that would be. Although the almaamy states were destroyed by colonialism and political dissintegration, thankfully, the vestiges of these kingdoms live on in places like Senegal today, where the authority of the scholars and saints is seen as transcendental to that of the modern state and still subtly retains perpetual sovereignty.

Invisible Lighthouse

In Khaled Abou el-Fadl's classic work, Rebellion and Violence in Islamic Law, he examines the historical development of juristic discourse on rebellion in Islamic law, essentially showing that there are two streams of thought in the Sunni legal cannon regarding this question: the obedience to the ruler school, and the school of Imam Hussain and his stance in the Battle of Karabala, which provides Islamic legal precedent to rebel against unjust rule.

The legacy of Suleyman Baal’s successful, institutionalized Atlantic-Islamic revolution behooves us to take more seriously the mechanisms of Muslim-led revolts throughout history, such as the Malê Rebellion in Brazil (1835) and the Darul Islam rebellion in Indonesia (1949) as notions of dissent that attempted to adhere to Islamic juristic principles. It was not all or nothing. Law was never enacted in a black and white manner. Muslim communities evolved along with new challenges such as slavery, corruption, colonization and had to respond to them accordingly in different locales.

In the book, The Magna Carta of Humanity, Os Guinness compares the American Revolution with the French one, and cites fundamental differences between them. For Guiness, the American Revolution was rooted in biblical principles, especially those found in the Exodus narrative and Sinai covenant. He centers the idea that freedom comes through covenantal responsibility—a Divine duty. Holding the view that people are prone to corruption and therefore power must be restrained and distributed, the American Revolution was centered on the ideals of ordered liberty, and change through deliberation, checks and balances. Freedom is linked to self-government under God, with the purpose of enabling virtue and justice.

Regarding the French Revolution, he views it as based on Enlightenment rationalism and secular humanism, rejecting divine authority in favor of human reason and utopian ideals. It propagated the belief in the perfectibility of man—that human beings can be remade through education, revolution, and reason. The French Revolution embraced violent upheaval, mob rule, and the guillotine as tools to rapidly destroy the old order and install a new one. To the French, freedom is seen as autonomy from all authority, especially religious and moral constraints—leading to license rather than liberty. Its culmination is the Reign of Terror, Napoleon’s dictatorship, and a legacy of revolutionary authoritarianism.

Guiness posits that America has taken a turn for the worst facets not of the American Revolution, but the French one. Clearly, he is right. We are living now through the horror show that is the 21st century Reign of Terror. The collapse of the liberal ruse-based order. All the supremacist feigning of liberté, égalité, fraternité has come crashing down, rearing its ugliest head on immigrants and Muslims, and those who are seen as outsiders to the supremacist Judeo-Christian worldview.

Today, we are experiencing an oligarchic, tech-elite led rebellion in the West: a techno-dictatorship guided by Dark Enlightenment, signaling the failure of the ideals of the American Revolution that undergird the very basis of Western Civilization. This globalist regime of hyper militarization, surveillance, supremacy and racism is inherently based on anti-Muslim animus. Humanity is more connected and technologically advanced than ever, yet the world feels crushed by the weight of oppression, supremacy and mass violence. And who is paying the highest price? The downtrodden people of Palestine, Congo, Sudan, Yemen, Kashmir, Lebanon and Afghanistan.

They have have declared: enough is enough. We need a different way. A new vision.

We are arguably living in neo-pagan, neo-jahiliyya times. Thus, we are living through the anti-thesis of Almaamy states: instead of the most knowledgeable, most moral being given positions of authority, the worst, most ignorant, most immoral fascists are in charge. Instead of protecting fundamental human rights based on every individual’s God-given sanctity, innocents are snatched up and dumped into unmarked vehicles by modern day enslavers, ICE agents and prison wardens.

Today, the human spirit itself needs to be manumitted.

The so-called Atlantic Revolutions of the 18th-19th centuries are thought to be the basis for the formation of the contemporary global world order: the creation of nation states, the dismantling of old colonial empires, and the widespread adoption of Enlightenment ideals like liberalism and republicanism. For so long, due to vicious anti-Muslim sentiment and racism, the dominant narrative of the Atlantic Revolutions has fashioned itself as a strictly “Judeo-Christian” story. By doing so, this narrative left out the three most essential elements to human and civilizational progress: the Qur’an, the legacy of black Muslims and the authority of the final messenger, the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ.

The Forgotten Atlantic Revolution can remedy blind spots not only in our understanding of America and the West, but of the role of Islam in the world as a whole. The pioneering Muslim scholars of West Africa are the invisible lighthouses not only of Atlantic history but, of Islamic and human history. More than ever, we need to seriously heed the ideals of the forgotten Muslim-led Atlantic rebellion of those who—in the colonizer’s own admission—based their ethics on light. Thus, when we ignore the legacies of the wise almaamys of West Africa, the neglected Philosopher Kings of Muslim history, we will continue to drown in a sea of darkness.

Their legacy of just scholarly rule based on the final revelation of God to humanity is the missing link in the story of modern history.

It is time to reignite the light of this invisible lighthouse.

Darkness upon darkness! If one stretches out their hand, they can hardly see it. And whoever Allah does not bless with light will have no light! (Qur’an 24:40)

Source: شيخ سليمان بال قائد ثورة فوتا تور / محمد يوري سل- المكتبة الإسلامية السنغالية, Timbuktu Editions, 2019.